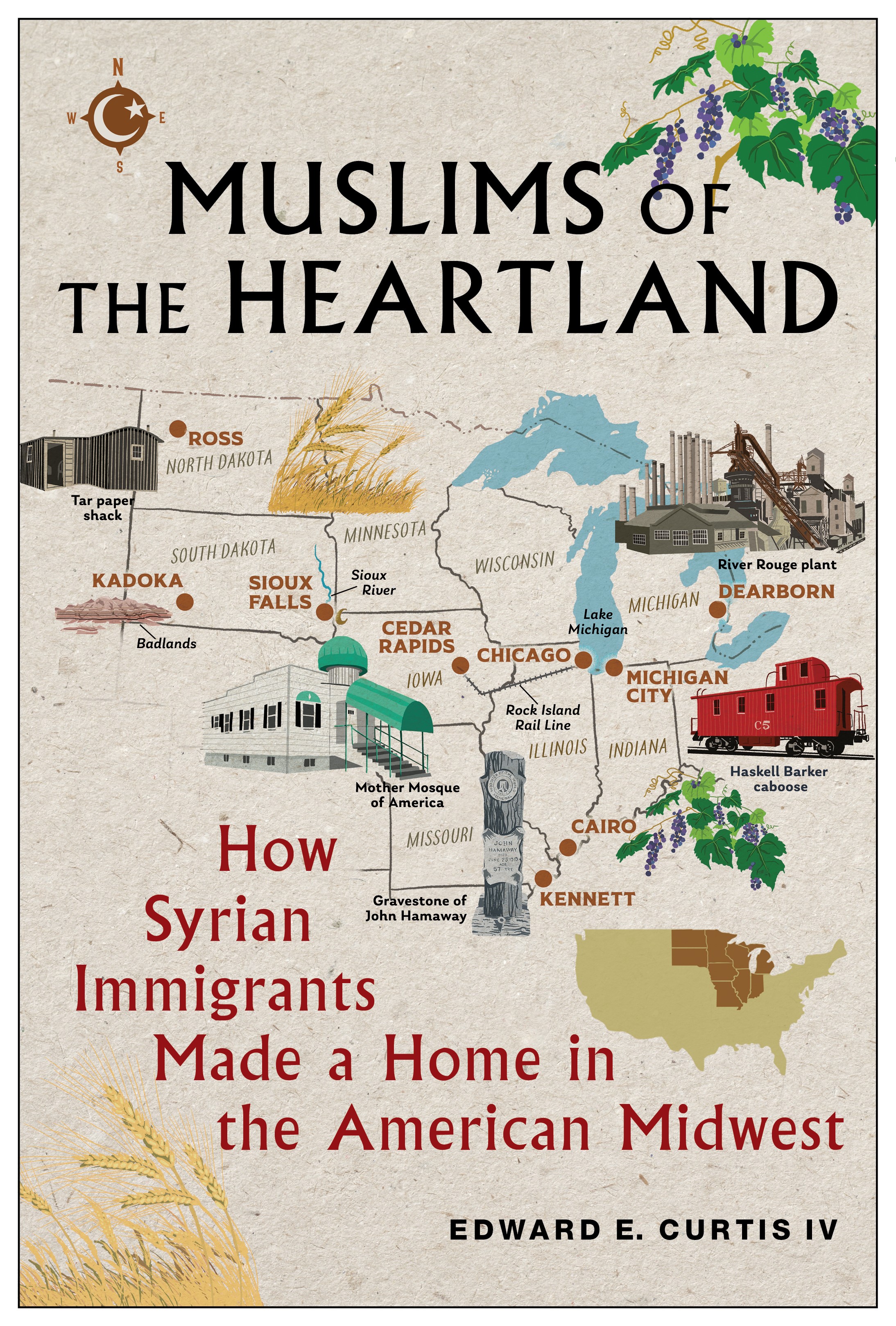

Dr. Edward Curtis, William M. and Gail M. Plater Chair of the Liberal Arts and Professor of Religious Studies in the IU School of Liberal Arts has been awarded the 2023 Evelyn Shakir Non-Fiction Arab American Book Award from the Arab American National Museum. Curtis’ book, Muslims of the Heartland: How Syrian Immigrants Made a Home in the American Midwest explores the world of the first two generations of Arab Muslims who settled in the Midwest in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, offering an intimate portrait of fifteen women and men who lived in the Dakotas, Indiana, Iowa, and Michigan.

“I shed a tear or two of joy when I received the news,” said Curtis. “It means so much that the book award comes from the Arab American National Museum.”

Of all the Great Lakes states, Indiana controls the smallest amount of shoreline. Just forty-five miles along Lake Michigan.

But that small slice of land has been essential to the state’s economic, social, and it turns out, cultural contributions to U.S. history.

It is home, for example, to one of Indiana’s most popular tourist attractions, the freshwater sand dunes formed over thousands of years by waves and winds from the country’s largest inland lake.

But it’s probably fair to say that when most Hoosiers think of the long-gone Hoosier Slide, the largest single dune along Lake Michigan, they don’t often imagine Arabic-speaking Muslims among the many tourists sliding down its two hundred feet of sand in the early 1900s.

This long lost chapter of Indiana history has now been brought to light by Edward Curtis, William M. and Gail M. Plater Chair of the Liberal Arts and Professor of Religious Studies. Curtis’ book, Muslims of the Heartland: How Syrian Immigrants Made a Home in the American Midwest, recently won the Evelyn Shakir Non-Fiction Arab American Book Award from the Arab American National Museum.

The first historian to detail Indiana’s early contributions to Islam in the United States, Curtis recreates what it was like along Lake Michigan for Arabic-speaking immigrants in Michigan City from the 1890s to the 1930s.

“They were among the half a million Lebanese and Syrians who left their native lands for the Americas before 1920,” Curtis says. They arrived in Michigan City to work at Haskell and Barker, a railroad car maker and Indiana’s largest employer at the time.

Most of them were Christian, but there was also a vital Muslim minority. In 1931, that Muslim minority made history by establishing what is the longest-running mosque in Indiana.

“Detroit is often associated with the history of Muslim Americans,” Curtis explains, “but this mosque, called Asser El Jadeed, predates any of the Arab Muslim congregations currently operating in Greater Detroit.”

Curtis hopes his research will reclaim Indiana’s stake in the larger story of Islam in America.

“This story,” he claims, “is about much more than religion, and the contributions of these immigrants will probably surprise a lot of Hoosiers.”

His book, for example, examines the role of Syrian Muslims in fueling Michigan City’s culture of wrestling. Older Syrians would train their young to compete in tournaments, which were a major source of entertainment for Michigan City residents in 1900. “Michigan City even hosted a fan club for a popular wrestler Yussife Hussane, whose wrestling moniker was ‘The Terrible Turk,’” says Curtis.

In addition, Curtis’ Muslims of the Heartland details how Michigan City’s first draftee during World War I was a Muslim man named Mohamed Debojah (Debaja), who served along with other Syrian and Lebanese immigrants, both Christian and Muslim, in both World War I and II.

Curtis, who himself is a descendant of Syrian-Lebanese immigrants who settled in Southern Illinois in the 1890s, says that the ultimate aim of this research is to encourage Hoosiers and other Midwesterners to celebrate the racial, ethnic, and religious history of the heartland.

“Some of us in the Midwest have . . . forgotten who we are,” according to Curtis. “The truth is that we have always been diverse. I hope more of us celebrate this multicultural heritage.”

Curtis will be honored during the Arab American National Museum award ceremony in November.