I did not move from the front of the family television on New Year’s Day, 1964, when No. 1 Texas and No. 2 Navy, with Roger Staubach, met at the old stadium on the grounds of the State Fair. It was a rare matchup of the two top-ranked teams, a circumstance that would morph from curiosity to requirement, only to become taken for granted. I refused to abandon the Midshipmen that day, even as a one-sided Longhorn victory turned a loyal Navy household very quiet.

Notre Dame got back into the bowl business here in 1970 after a 45-year pause, and in 1978 woke up as a No. 5 team, upset Texas, and landed at No. 1. When Baylor won its first Southwest Conference championship in 50 years and played in the Classic for the first time in 1975, there was something in the way Lindsey Nelson said the Baylor Bears that captured how much that appearance meant.

But the disintegration of the Southwest Conference gradually made most Cotton Bowl matchups less relevant, and the bowl assignments with championship stakes always took me somewhere else.

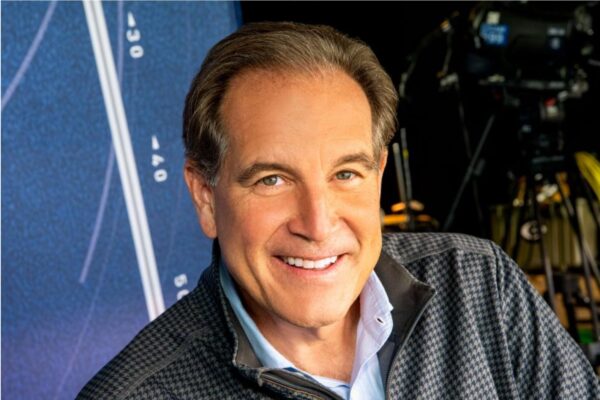

Jim “Hoss” Brock helped the Cotton Bowl become known for its hospitality. (Ian Halperin | CBAA)

The most challenging aspect of Brock’s work in the wild west days of college football took place in the smoke-filled rooms of an industry built upon cajoling, seducing, deal making and breaking, and all the other tactics that have somehow begun to appear charming in hindsight.

Hoss would say he could tell where his negotiations stood with a given institution of higher learning by the location of his assigned parking spot on an autumn Saturday. If the Cotton Bowl had an inside track with his targeted attraction, Hoss could practically hopscotch from his rental car to the press gate. If he had to walk ten blocks – uphill — he knew he better have a Plan B.

In 1984, as Boston College’s Doug Flutie was on the way to a Heisman Trophy in his senior season, Hoss turned the recruitment of the Eagles into a crusade. Much of the northeast had withdrawn from the business of big-time college football. Here was a chance to secure that rare, entertaining talent that had inspired the I-95 corridor and all those ratings-driving eyeballs.

His chase began a year early, according to author Steve Richardson’s history of the Cotton Bowl, which quoted Brock as telling Flutie “to keep us in mind, because we might be talking to you next year.” Helped by the first $2 million payout in the history of the Cotton Bowl, the deal was done. When the Boston College administration finally committed, Hoss wanted to tell his friend and competitor, Mickey Holmes of the Sugar Bowl, that the chase was over. Their conversation, according to the industry’s urban legend, took place as the two stood side-by-side in a urinal.

Hoss was at the peak of his influence, recruiting three Heisman winners in a four-game stretch: Flutie, Auburn’s Bo Jackson and Tim Brown of Notre Dame. More urban legend: On one of his many trips to South Bend, when Hoss was asked about the wisdom of being out and about at 4 a.m., he is said to have replied that in Dallas it was only 3 o’clock.

His sales pitch could never include the splendor of Pasadena on New Year’s Day, or Miami’s sunshine and beaches, or the domed environment in New Orleans and all those libraries and museums on Bourbon Street.

What he sold was Texas and its hospitality, which is on display this week. The first College Football Playoff National Championship was in Arlington last January, and on New Year’s Eve the 80th anniversary Cotton Bowl Classic will take its place back at the table with the cool kids. Each time a visitor feels welcome from here to Arlington, or a reporter’s job is made a little more convenient by the organization’s remarkable attention to detail, the Brock legacy will extend one more day. He entered the Cotton Bowl Hall of Fame in 2005, with a class that included Troy Aikman of UCLA, Lance Alworth of Arkansas, Lydell Mitchell of Penn State and former Texas A&M coach Gene Stallings.

Not that his diplomacy extended to everyone. Richardson’s history includes an episode that took place during a meeting of the old Big Eight conference in Colorado Springs. Tom Starr, a former bowl executive, remembered an exchange at the Golden Bee, a spot across from the Broadmoor Hotel, that took place as the two stood at adjacent urinals.

“There was a piano bar sing-along with an old-time piano player,” Starr told Richardson. “Hoss got up on stage and was whistling the ‘Yellow Rose of Texas.’ There was a woman sitting near the stage, and she said, ‘Your whistling hurts my ears.’ And she squeezed her hands tightly around both ears. Hoss responded: ‘Well, Darlin’, your face hurts my eyes.’”

Brock’s passing in 2008, at the age of 74, left a permanent void in an industry that would one day make a whole lot more money, but never have quite as much fun.

— Malcolm Moran | @malcolm_moran